See Us Heal

Originally published in the 10th issue of The Bikepacking Journal, “See Us Heal” is a powerful short piece from Eric Arce that follows three BIPOC mountain bikers on a trip to Crested Butte, Colorado. It broaches the subject of mental health by dispelling the notion that riding is therapy and highlighting the critical importance of vulnerability and connection. Find Eric’s insightful story and a spectacular set of images here…

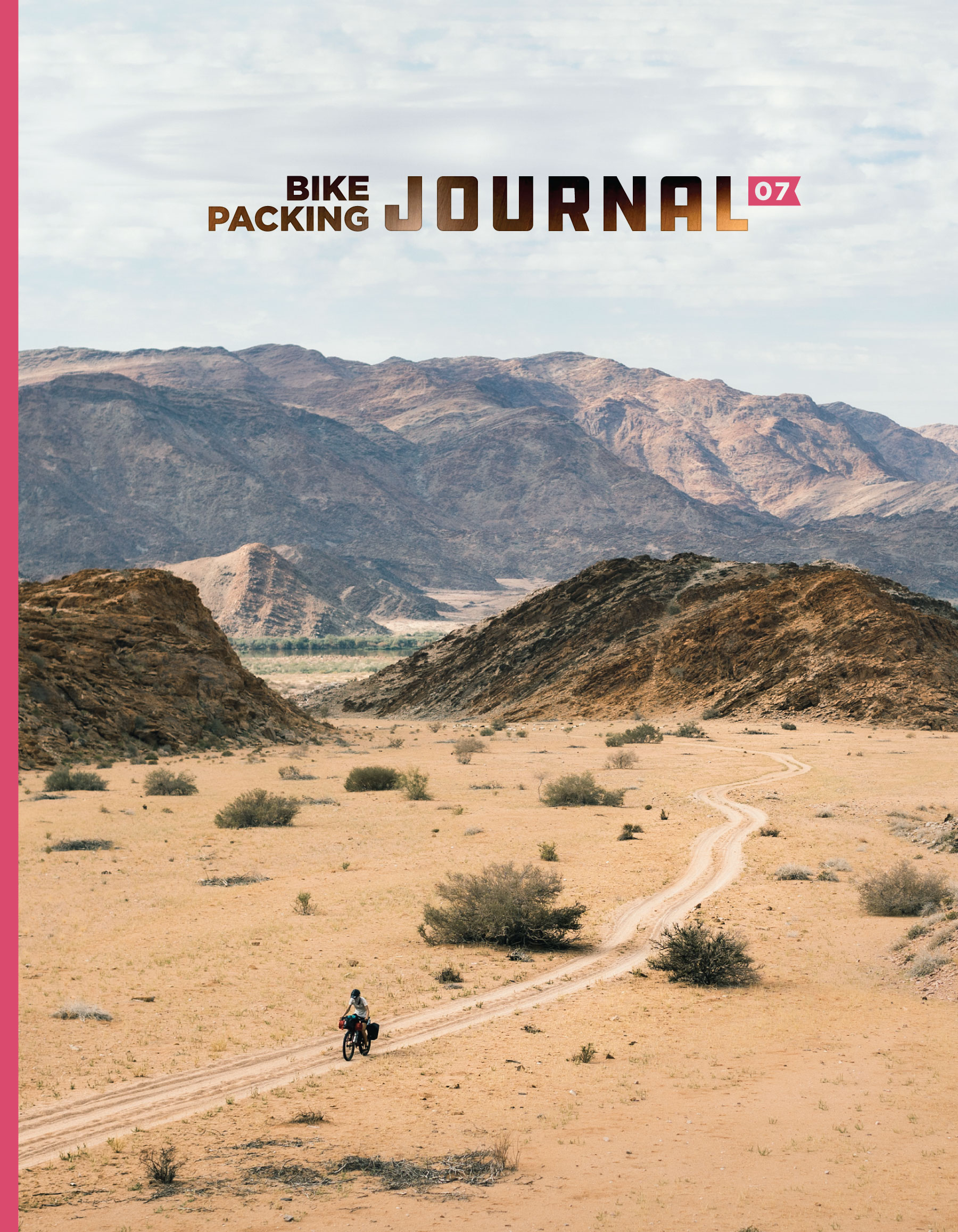

After riding all day, I stop by the river to refill my water bladder. Before I crouch down with my filter, I take a deep breath to soak in the alpine views. It’s the height of summer, and I’m on a dreamlike bikepacking trip in Crested Butte, Colorado, with my good friends Jalen Bazile and Evan Green. Traversing this landscape by bike releases a mixture of endorphins and serotonin that cultivates immense joy. But I know these brain chemicals won’t last forever.

We’re here to make a short film titled See Us Heal that aims to create more vulnerable spaces for everyone who rides bikes. This project centers on having candid discussions about our emotions and the importance of being honest about our mental state. In the film, I discuss mental health and how it’s a challenging subject to broach. There is no question that mountain biking is beneficial to our psychological well-being and can help us with our moods, but the subject of mental health is complex and far deeper than this. I’d like to elaborate on some of the points I made in See Us Heal and also provide a bit of nuance to the narrative that mountain biking is therapy. While partially true, it’s an overly simplistic approach to the possibilities of cycling to address serious mental health issues. Riding has helped countless people, including me, improve their moods and curb stress, but a bike still isn’t a substitute for addressing acute issues that require therapy, medication, or long-term solutions.

A Project in Support of Vulnerability

After driving from Salt Lake City, Utah, I arrive in Crested Butte to meet up with Jalen and Evan and flesh out the logistics of the trip. We’re happy to see each other. The three of us have been friends for a while and have admired our respective efforts in the cycling community. Jalen is a multi-talented outdoor guide and builds community by doing essential work with the Black Foxes, creating spaces for fellow Black cyclists. Evan Green, a fellow adventure photographer and videographer, creates beautiful visuals of landscapes and people. Evan will do the video and editing for this project. As for me, I’ll take the still images. I’ve been looking forward to working together, so I’m happy it’s coming to fruition with them and in this location.

Set against the backdrop of towering mountains, Crested Butte is beautiful. I’ve been here once before in the fall. The vibrant colors, the long and winding Snake River, and the purple-hued mountains all combine to provide a photographer with incredible biking landscapes. Crested Butte is visually stunning, and nature has a calming effect, helping us to open up emotionally. Except for the horseflies, this place is the perfect setting for a memorable project.

As we’re packing all our gear, making sure we have everything from camping gear to camera equipment, we start discussing the topics we want to include in the film. Do we have an underlying theme? How do we create something meaningful and different within cycling culture? Without question, we want to show how we can move across beautiful places in ways that allow for healing, growth, and introspection—things we need to find our version of happiness in the midst of personal struggles and systemic challenges.

Jalen, Evan, and I are very different and each ride for our own reasons. One thing we share is a desire to foster vulnerability and create pathways for more candid discussions. In the film, I discuss the topic of mental health. Often, people talk about this subject in vague terms, which is understandable because it’s such a deeply intimate topic and can be surrounded by feelings of shame. As someone who relies on mountain biking to improve my mood, riding has done wonders for me. Riding has changed my life for the better, but I don’t want to romanticize its ability to heal.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term

I’m not here to discourage people from using mountain biking to feel better by going into nature or to escape the societal pressures that often hamper our optimism. We need to get away sometimes to feel recharged. Without a doubt, my time spent on a bike has brought immense joy to my life. Ever since my first mountain bike ride, I’ve been hooked because of its myriad physical and emotional benefits.

Numerous health research institutions, such as the National Library of Medicine and the American Psychological Association, describe how beneficial exercise can be in reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. Mountain biking is a great way to move our bodies and has several unique qualities to curb mental health issues. For one, mountain biking takes place in nature, which has a calming effect on the mind. Spending time outdoors improves our overall well-being. Secondly, mountain biking can be challenging. Riders constantly face technical features like difficult descents and climbs and learn to appreciate the little victories of navigating a rock garden or clearing a jump. Overcoming challenges that require practice can eventually build confidence. Lastly, I’ve met some of my best friends through mountain biking. If you find your community through cycling, it helps reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness. Social support is important for mental health.

Mountain biking’s ability to provide short-term boosts of happiness makes us want to return for more. That’s why we do it, right? It’s fun, and it provides an emotional high when endorphins are released during exercise, causing a feeling of euphoria. Endorphins are natural chemicals produced by the body that act as painkillers and mood boosters. After a bike ride, it’s hard not to feel like short spikes in our moods are going to resolve all our emotional issues when we’re struggling.

While mountain biking has given me life-changing insight, it still can’t help us process complex emotions that are rooted in trauma, or identity issues, or unlearn the ways we can cause others harm. There is a misconception that bike rides and their short-term chemical releases will address long-term problems, and I want to move beyond the idea that exercising or being on a bike is therapy and that pedaling alone can lead to healing. There’s a difference between doing things that give us temporary increases of joy and taking concrete steps that can address long-term mental health struggles.

If, as cyclists, we are saying pedaling is therapy, how exactly does a bike ride confront the things we are dealing with? A bike ride is temporary, and once it ends, we have to grapple with the emotions that made us want to grab our bikes in the first place. Narratives that discuss cycling as the main solution to address mental health issues worry me. If left untreated, mental health issues can have serious consequences. The longer you wait to deal with those issues, the worse it can get. I speak not from a holier-than-thou position but from humble experience: I once put a lot of stock in mountain biking’s ability to address my mental health, and yet it didn’t cure my anxiety and depression. For me, it wasn’t until I began processing my feelings through therapy, medication, mental health studies, and books from professionals that I began to understand the root causes of my struggles and how to mitigate them.

Leaving an Old Dream Behind

After entering the fourth year of my Ph.D. program studying intense topics of race and immigration, I wanted to quit. I kept telling myself that I was almost done, and I tried to convince myself, again and again, that I could get through it. I sat in the living room of my apartment, listing off the reasons why I needed to stay in my program: What would people think? I don’t want to feel like a failure. I feel like I’m letting my community down.

In the middle of these thoughts, laden with shame, I started thinking of ways I could relieve my stress, which, in fact, was a creeping depression. As the negative thoughts constantly attacked my health, I felt like being alone more and more and had increasing difficulty finding joy in everyday things. After a few years off from mountain biking because of a major injury, I figured it would be productive for me to invest in a bike again.

Without much money as a graduate student, I needed an inexpensive way to get back into mountain biking, so I bought an entry-level hardtail just so I had something to pedal around on blue trails. I previously raced downhill, but it had been six years since I last owned a mountain bike, and I was elated to be back on the saddle. My skills were a little rusty, but I had fun. I loved the scenery, how my body felt after pushing my limits, and the boost to my confidence after a challenging feature. Riding helped me feel recharged every day, but eventually, the honeymoon phase ended. The depression didn’t go away; it had only temporarily subsided. Pedaling kept me from falling into a deeper form of depression, but I was depressed nonetheless, and I found it a little harder to get out of bed every day.

I kept trying to fight off the uncertain tension between wanting to finish a degree I put so much work into and wanting to leave an environment I had discovered wasn’t for me. What made it especially difficult was that part of my ethnographic work included interviewing immigrants of color who worked two to three jobs, often under violent conditions. I’d hear their crushing stories. I kept telling myself that I was so privileged. What do I really have to complain about? I knew I would eventually need professional help to grapple with these feelings and questions. No amount of bike riding would help me understand how to deal with my depression.

I had the luxury of being a university student, which afforded me access to a psychiatrist who prescribed medication and to a therapist who helped me process my emotions. There were times I went to my therapist twice a week. In her office, she helped me understand what I wanted to do with my life so I could resolve the tension that had weighed on me tremendously. I grappled with a traditional perspective on quitting, which made it seem like an ultimate failure and generated a lot of shame.

Weeks turned into months of therapy, and I slowly climbed out of my depression. My bike rides were that much better once my mood improved because I began to let go of shame, which was like a dark cloud even on my rides. I remember during one of my therapy sessions, my therapist asked me what I’d like to do as a career after graduate school, and I responded, “I’d like to be a photographer, but I know that’s impossible.” Yes, she helped me work through that too.

In Support of Bikes and More

Evan, Jalen, and I turn another corner on our bikepacking trip in Crested Butte, and again we want to stop and soak it all in. This time, we see a lush forest with the light hitting the trees at just the right spot, illuminating the scenery perfectly. We all look at each other as if to say, We need to stop to capture this. I think about how happy I feel at the moment and how riding provides such beautiful moments for me to revisit.

As I’m soaking in the quietness of being in the backcountry, an alert on my phone rings to let me know to take my anxiety medication. I take it before I forget and carry on with everything else. I’m happy with the mental place I’m in now. I’m happy that I’ve gotten to a point where I can mitigate emotional situations that I struggled with in the past.

I love riding for the joy it has given me over the years, but I’m also thankful that I recognized that it’s okay, and often important, to get additional help from professionals. While society still has a way to go, I’m glad it is more accepting of mental health struggles, particularly for men of color.

Interested in more stories like this one? Enjoy inspiring writing and breathtaking photographs, all in the full glory of print!

- Twice yearly – New issues are released in April and October of each year.

- Free shipping – Shipping is on us, anywhere in the world.

- Carefully crafted – We've worked hard to create something beautiful and lasting.

- Limited edition – We print one copy for each of our members, and not many beyond that.

- Only in print – There's nothing quite like savoring stories and images on paper.

- Truly independent – This project wouldn't be possible without our members.

- Member Support – Sustains this website and all the content we publish.