Stooge MK6 Review: (Not) Using Technology

After a lot of waiting, we finally got ahold of a shiny new Stooge MK6 and proceeded to get it dirty while putting tons of miles on it throughout all manner of trail rides and bikepacking trips around the Appalachians. Find an extensive write-up on the MK6 featuring some Stooge history, a rumination on riding rigid mountain bikes, loads of photos, and an in-depth review here…

PUBLISHED Nov 16, 2023

With riding photos by TJ Kearns

I’ve been eager to throw a leg over a Stooge since we first announced the Scrambler in June of 2020. I was already familiar with the brand, but the adventure-oriented Scrambler spurred an obsession. Not too long after, I contacted the brand’s owner, Andy Stevenson, only to find out they sold out in three weeks. I can’t remember exactly what drew me to that bike—whether it was the distinctive klunker vibe, that raked-out bi-plane fork, the signature twin top tube, or just the brand name. Anyone familiar with the Stooges’ 1969 self-titled album or Fun House and Raw Power from the early ’70s will understand the allure. I mean, c’mon, those lively clap tracks in “1969” and “No Fun” masking a sludgy punk rock undercurrent. And the cerebral riffs on “Dirt” or the better-known “I Wanna Be Your Dog” and “Gimme Danger.” No music better embodies riding a rigid steel mountain bike through the woods with reckless abandon.

Andy later reached out with the opportunity to try a Scrambler, but I opted to wait for the latest iteration of the Stooge, the Stooge MK6. The Scrambler and Stooge share similarities, but the Stooge is designed around 29” tires, whereas the Scrambler is a 27.5+ bike through and through. The Scrambler, originally dubbed the Adventure Stooge, is also slightly more tailored for bikepacking with its larger front triangle, full complement of rack and cage mounts, and steeper head angle for more neutral handling with front loads. While I appreciate these features, 29ers better suit my style, and the Stooge has many of the same bells and whistles and a more compelling geometry. Fast forward a couple of years—my, how time flies—and Andrew got in touch about sending a brand new Stooge MK6 across the pond for me to try out in the Appalachians. Look out, honey, ’cause I’m [not] using technology…

A Brief History of Stooge

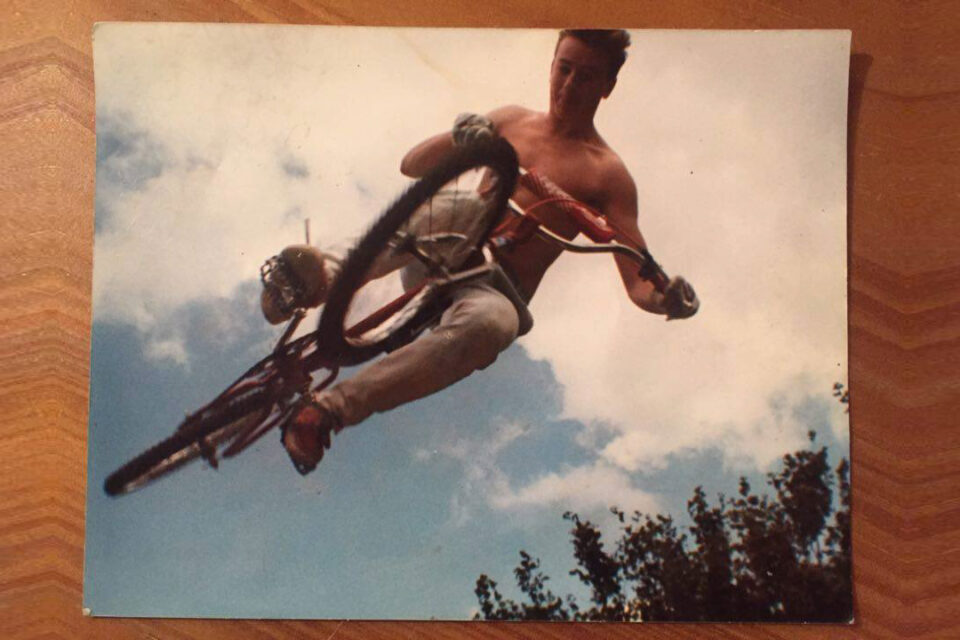

The origin story behind Stooge Cycles is rooted in the same sense of nostalgia and wonder that first drew me to the brand. Some might think Andrew has a design and engineering background, but that’s not the case. What he does have is a lifelong history in BMX and mountain biking and an absolute obsession with rigid mountain bike geometry. “I remember building a downhill BMX with 24-inch forks and massive Renthal handlebars and marveling at how the longer fork transformed the bike when belting down the side of a Welsh mountain. That was a pivotal moment,” explained Andy when I asked how Stooge got started.

That was just the pre-origin story. Jump well into Andy’s adulthood when the company started to take shape in North Wales circa 2013. At that point, he’d worked at a large local bike shop and got to try out all the latest modern mountain bike tech and toys. He eventually got bored with it all and started riding rigid bikes again. However, he saw a lot of limitations in contemporary bike geometry—especially as it pertained to rigid bikes—and decided to design the frame that he wanted.

For most people, the buck would have stopped there with one custom bike frame, but Andy continued his project. He ultimately spent a hefty sum to have a prototype made by the same manufacturer that builds Surly’s frames. The design harkened back to Andy’s BMX days with twin top tubes that paid homage to the Torker and Dave Parks bikes from his youth. It had a tall front end and a slack head angle compared to many other bikes at the time. When the frame arrived, he was blown away by how well his creation rode and handled.

“At this stage I had no idea how to run a bicycle company, but that didn’t stop me from spending every penny I owned and more on 100 more frames,” Andy added. Six months later, they arrived and, to Andy’s surprise, began selling. Andy mentioned that he owes many thanks to several folks who are now in the bikepacking scene, including Charlie the Bikemonger, who stocked those early frames in his shop, and Stuart Wright from Bearbones Bikepacking, who showcased a frame at The Welsh Ride Thing event.

As for Stooge, Andy said he recalls being stifled when trying to figure out a brand name. One day, he was sitting in his lounge admiring a Stooges concert poster he got at one of their shows. “There it was, Stooge,” he said. “It just rolled off the tongue, was nicely oblique, and fit in with my love of garage rock.”

A Brief History of The Stooge

Now based in Oswestry Shropshire, England, Stooge Cycles is still a one-person company. Andy’s approach to frame production follows the same straightforward model that led to the company’s creation: making single frame designs in limited batches, each announced one at a time, as they happen. Stooge has several mainstay frames in its catalog now, including the Scrambler, Dirtbomb, drop-bar Rambler, and the original, the Stooge (MK series). There have been six iterations of the Stooge, and with each one, Andy makes a few subtle refinements that move it toward his mission to craft the ultimate rigid mountain bike.

That first and only production run of the Stooge MK1 arrived in June 2014 and was specifically designed around a 29 × 3.0” front tire and a 29 × 2.3” rear. It was only available in one size: 18″ with a 597mm effective top tube length (ETT)—Andy’s size. The MK1 through to MK3 all shared more or less the same geometry: a 69-degree head angle, a 72-degree seat tube angle, and the same 597mm ETT, though the MK3 was also available in a 20” frame with a 635mm ETT. The MK3 also got a few other changes, such as a 44mm head tube, a shorter 430mm chainstay, and clearance for 27.5 x 3.0” tires.

With the MK4 in 2019, Andy made a few radical changes, including a much slacker 66-degree head tube angle and a straight steerer tube, so suspension forks were no longer an option, and Andy wouldn’t have it any other way. Additionally, the MK4 got a new rigid bi-plane fork with an eyebrow-raising 80mm offset. That gave it an unapologetically long wheelbase and pushed the front wheel way out in front of the cockpit. At the time, Andy was swimming against the industry current as bike companies were pairing slacker head angles with shorter fork offsets to improve handling. However, rigid bikes are different, as Andy asserted with this release. The frame was optimized for a 29 x 3.0” front and 29 x 2.6” tire combo. This was a revolutionary make-or-break moment for the company, and fortunately, the saga continued.

The MK5 saw a few significant changes. For one, it adopted the de facto Boost 148/110mm axle spacing standard. It also nixed the MK4’s extraordinarily long fork offset, which was replaced with the same 57mm offset bi-plane fork as the previously released Scrambler. This was mainly to tone down the steering and optimize it for 27.5+ tires. It also came equipped with a few more rack and bottle mounts.

The Stooge MK6

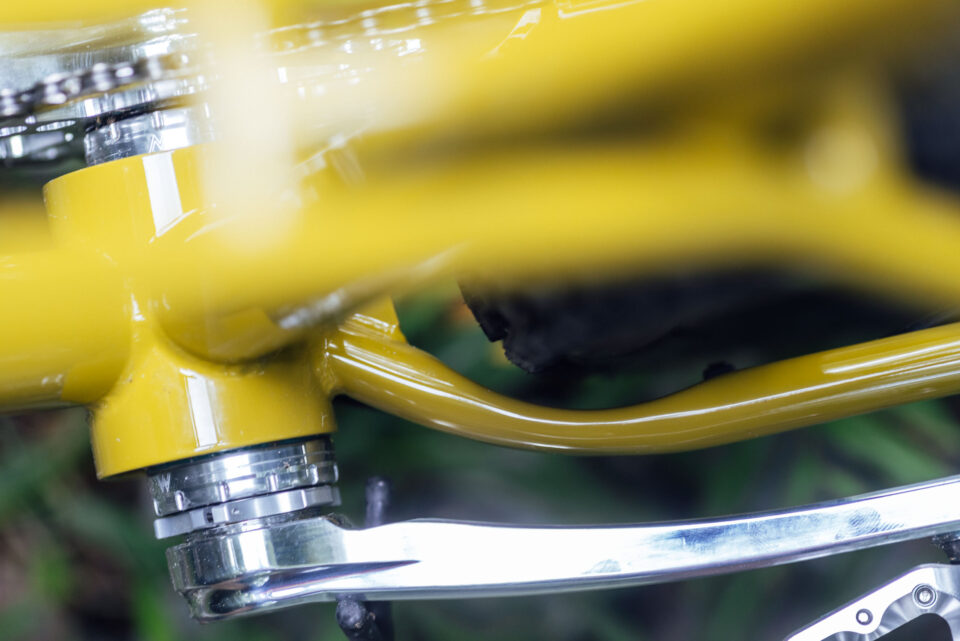

The metamorphosis continued when the Stooge MK6 was introduced this past summer. This batch received several minor tweaks and refinements, including a straight seat tube to accommodate longer dropper posts and added space at the yoke and seat stays to squeeze in a slightly more voluminous 29 x 2.8” rear tire. Although, as you can see in the photos below showing 29 x 2.6” tires on 31mm rims, a 2.8” tire would be pretty tight.

The most significant change to MK6 was up front. The stately curvilinear bi-plane fork used on the Scrambler and MK5 was traded for a straight-legged, segmented BMX-style fork. It maintained the same measurements, including the 57mm offset, but the aesthetic is completely different. This fork overhaul was a byproduct of how this bike was being used. Andy started getting emails from people wanting “rigid enduro bikes” after athlete Matt Larkin put on a show during the UK’s Southern Enduro series in 2020. Matt posted some pretty impressive results on the MK4, which garnered a lot of media coverage, including a bike check published on Pinkbike. This led to a few fork issues and the realization that although the bi-plane fork was tested to MTB standards, it wasn’t designed to withstand massive road gap jumps. In short, people were using the MK frames outside of the fork’s upper limit.

I really wanted to photograph that lovely bi-plane fork, and I was also a little shell-shocked (literally) from the relatively harsh segmented fork that was on the Black Mountain La Cabra I’d tested a few months prior. But after hearing a report that the old MK fork was indeed a little noodly when ridden hard, I was content with the new one, and I’ve been happy with it on the trail, which I’ll dig into later.

Tubeset and Ride Feel

All of Stooge’s steel frames are made in Taiwan from double-butted seamless 4130 Chromoly tubing. Andy admitted that he’s not a snob when it comes to tubing. “I come from a time when 4130 was some kind of magic number. If it was good enough for Haro and Torker and JMC, then it’s good enough for me,” he said. He wants his frames to remain affordable and says that geometry and longevity are his priority. There’s a general preconception, which is apparently amplified in the UK, that a tubeset with a Reynolds sticker is a better bike, but that’s not always the case. I’ve had many a bike prove that wrong, including the Tumbleweed Stargazer, which is one of the better steel tubesets I’ve ridden. There’s a lot more to it, including the gauge of tubing, shaping, and geometry.

That being said, at 10.5 pounds (4.8 kilograms), this frameset is no slouch. To put that in perspective, my Nordest Sardinha frame and fork weighed 9.7 pounds (4.4 kilograms), and it’s on the heavy side for a steel dirt touring frame. Once I finished the build and bolted on the pedals, I was half expecting a sluggish and tank-like harsh ride. That was quickly proven otherwise. I was pleasantly surprised to find that the MK6 frame has a lively feel that’s not harsh by any means and not heavy seeming or sluggish, either. It reminded me that I’d asked Andy why he went with a twin top tube design. He jokingly responded that, “The force of the rear wheel impacts travel all the way up the twin tubes to the headtube and cancel out the resultant vibrations felt through the seat of the pants.” After spending some time on the MK6, I now wonder if there might be a slight bit of truth to this. I’m largely kidding, but not about how supple and light this frame feels.

Like most of Andy’s frames, the MK6 uses an eccentric bottom bracket (EBB). Some might prefer a sliding dropout, and that might lighten up the frame a little, but Andy has stuck to his guns on this to not only keep the rear wheel in a fixed position but to seal the bottom bracket from the elements. This is a logical approach coming from a UK-based mountain biker. I was skeptical of EBBs at first, but after riding this bike for a while, I’m fine with it. In other words, I’d rather it be there than not because of the ability to convert the MK6 to singlespeed.

Sizing

The Stooge MK6 is available in two sizes, 18” and 19”, which basically equate to medium and large. Andy admits that folks at either end of the height spectrum are not well catered for, but Stooge is a one-person show, and this is the economy of scale in action. That being said, the MK6 has a much lower standover height than most frames of the same nominal size. Some people will appreciate the versatility in this, and others (like me) might want a little higher top tube for frame triangle space. Either way, the top tube height is more akin to a small size frame, so Andy suggests that the 18” will fit anyone from about 5’6” up to 6’0” tall. I’m 6’0” but opted for the 19”, which is for folks from 5’11” to 6’2” tall. I’ll talk a little bit more about fit when I dig into the ride.

Build Kit (My Stooge MK6 History)

I’ve had the Stooge MK6 for several months now, long enough to put a lot of miles on it and reconfigure it several times. I initially built it with a wide-range 1×11 drivetrain and rode it in that permutation for a few months. I climbed a bunch of challenging stuff, rode my local trails backward and forward, went bikepacking, and took it down some chunky lines that rigid mountain bikes might normally shy away from. I set it up with three distinct tire combos and tried it with three different handlebars. I also rebuilt it as a singlespeed, which is how it’s currently configured and how it will probably remain. Here’s the original build kit:

- Frame 20″ Stooge MK6, Yellow

- Fork Stooge MK6

- Wheels Industry Nine Hydra Enduro S Carbon

- Front Tire Maxxis Rekon+, 29 x 2.8″

- Rear Tire Maxxis Rekon, 29 x 2.6″

- Crankset White Industries M30, 170mm

- Derailleur Shimano XT 11-speed

- Shifter Shimano XT 11-speed

- Cassette Garbaruk 11-50t

- Bottom Bracket White Industries

- Handlebar Stooge Junker Bar

- Grips Ergon GA3, Large

- Headset Chris King

- Brakes Hope Tech3 E4

- Saddle Ergon SMC Core

- Seatpost OneUp V2, 210mm

This build came in at 30.8 pounds (14 kilograms), and I was pretty content with it, but I ultimately changed a few things. First, I went from the White Industries cranks to my trusty Cane Creek eeWings. I was a little bummed about this, but the White Industries cranks had a horrible creak that I couldn’t get rid of. I’m still trying to resolve this. Second, I swapped handlebars a couple of times after starting with Stooge’s own Junker Bar, a retro 820mm-wide BMX style 4130 bar with a 20-degree backsweep and 85mm rise. I was pleasantly surprised by this bar. It’s heavy, but it’s not as harsh as I would have expected from a cross-braced chromoly handlebar. Its massive rise also worked well for the upright posture that the M6’s short top tube afforded. However, I wanted to play around with this bike and lighten the front end, so I later tried the Whisky Milhouse and ultimately moved the stem up 20mm and installed the 38mm-rise Doom Bikepacker’s Delight. It’s a little lower than both the Milhouse and the Junker, but I’m enjoying it.

The biggest and best change was a move from the 2.8” Rekon up front to a 3.0” Maxxis Minion DHF. This tire is incredible. When mounted to a wide rim, you can run it at ~12PSI and still have plenty of sidewall support and, more importantly, traction for days. I’m pretty convinced that the MK6 was meant for this tire combo. If I were doing it over again, I’d have built a different wheel for the front, one with a wider rim in the 36-40mm range. 29+ ain’t dead! Other components to note include three trustworthy regulars: Hope Tech 3 E4 brakes, Industry Nine Hydra Enduro S Carbon wheels, and the OneUp dropper post.

Apples vs. Pears

Rewinding to my first ride on the Stooge, I recall being worried about inflated expectations. After all, this was a bike I’d been waiting to try for several years, not to mention one that was intentionally designed to be fully rigid and still be as capable as those with suspension. At the same time, I was also concerned that the fork would be too harsh, the bike would feel too heavy, and that it would be too short. The Stooge MK6 only comes in two sizes, and the larger of the two has an effective top tube length that’s two or three centimeters shorter than many of the other long, low, and ultra-slack British hardtails I’ve been feverishly testing over the last couple of years. I’ve ridden a lot of rigid mountain bikes over the years, but most were not in the same category as the Stooge. Indeed, very few bikes are.

| Size | 18″ | 19″ |

|---|---|---|

| Effective top tube | 610 | 625 |

| Seat Tube Length | 457 | 483 |

| Head Tube Length | 150 | 157 |

| Chainstay Length | 445 | 445 |

| BB drop (+/-7mm) | 60 | 60 |

| Fork A/C | 455 | 455 |

| Fork Offset | 57 | 57 |

| Head Angle | 66° | 66° |

| Seat Angle | 74° | 74° |

| Reach | 438.4 | 451.4 |

| Stack | 598.4 | 605 |

It immediately felt short, but I had zero issues with fit. The riser bars and cockpit created a more upright posture that surprisingly just worked. This is where things get interesting—comparing apples to pears. The closest bike I could compare the MK6 to was the Nordest Sardinha. They’re hardly similar, but I spent a lot of time riding the Nordest fully rigid and loved it in that guise. To put things in perspective, the Nordest has a 36mm longer reach and a 34mm longer effective top tube. Here’s the kicker: the Stooge only has a 7mm shorter wheelbase. To get to the meat and marrow of the MK6, you first have to talk about what it means to ride a rigid mountain bike.

On Riding Rigid

As I spoke about at length within my recent Transition Smuggler review, modern suspension bikes—both full-suspension and hardtail—have achieved ridiculous levels of capability in recent years. They’ve been retooled with front-end geometry that prioritizes high-speed stability via super slack head angles, steep seat tubes, long front-centers, and reduced fork offset. These bikes are explicitly engineered to confront and tame trails head-on at remarkable speeds, emphasizing the pursuit of velocity and amplitude and effectively dumbing down obstacles that would slow your progress. Whether you possess the skill or inclination for the intense riding these bikes are tailored for, opting for a progressive hardtail or full-suspension trail bike means embracing this high-speed, trail-devouring intention, at least to some degree. Obviously, these big statements are less applicable to hardtails and can even be put on a sliding scale with full-suspension bikes based on the amount of travel, but you get my drift.

A rigid mountain bike is a horse of a completely different color. When riding rigid, it’s not about speed and there’s nothing smoothing out the trail other than your tires. Riding a rigid mountain bike fosters a connection with the trail, warts and all. It’s more like a dance. Trail riding becomes a meditation that requires constant anticipation and reaction, harnessing an endless pattern of obstacles, rocks, roots, ride-outs, and undulations, all to string together a fluid composition that yields a perpetual sense of gratification. While some people think riding a rigid mountain bike is masochistic, that’s far from the truth. It simply reflects a different way of riding. It’s about movement, not speed.

The Stooge MK6 is a master of this language like no other bike I’ve ridden. The essence of the MK6’s geometry concept revolves around creating a front end that’s capable of swift directional changes, especially at higher-than-usual speeds (in rigid bike terms) and nimble enough to shift weight rearward, allowing the front to effortlessly skip across lips, bumps, and rocks. At the helm of this is the MK6’s 66-degree head tube and 57mm fork offset. Sixty-six degrees is positively progressive, particularly for a rigid mountain bike. Traditionally, the slacker the head angle, the slower the steering and the greater the wheel flop. That’s where the fork comes in. Its 57mm fork offset was conceived to speed up the steering and lessen the wheel flop. At first it almost felt too quick, but once I reprogrammed the “long-low-slack” muscle memory I’d developed, it clicked.

The longer fork offset positions the rider further behind the front axle rather than over it. This, combined with the relatively short cockpit, allows you to quickly move rearward and lighten the front end when needed. It’s also not shy on steeper and more technical terrain. This is owed just as much to the long wheelbase as it is the slack head tube angle, which is one of the more unique and interesting parts of this bike—the short cockpit and long fork offset keep things quick and nimble, and the long wheelbase and slack head tube reinforce confidence and stability to create a unique balance. In short, it’s a sum of its parts that all work in concert to execute the dance that I waxed on about earlier.

To my surprise, the MK6 was also one of the best-climbing mountain bikes I’ve tried in a long time. On a few rides, I consistently impressed myself with how fluidly and easily I cleared certain technical step-ups and lines. Much of that is owed to the Stooge’s planted and well-balanced stance, which again is likely owed to the relatively short cockpit combined with a long wheelbase. It also seems to have unlimited traction, particularly when seated. It’s one of those bikes that you feel like you can ride slow technical trails on for days.

While Out Bikepacking

This section will be relatively brief, as I’ve already relayed how the MK6 differs from the Scrambler. It has most of the mounts I need: eyelets for front and rear racks, three-pack mounts on the fork blades, and another triplet on the downtube. As seen in many of these photos, the twin top tubes are handy for lashing on random gear. I wish it had provisions for a cage on the underside of the downtube, though. And if I’m splitting hairs, I might raise the top tube by a couple of centimeters to accommodate a larger frame bag, although the custom Rockgeist frame bag shown here has plenty of volume. Two rack eyelets on the inside of the fork legs would also be nice. That would allow fork cages to be used in conjunction with a front rack.

Still, I wouldn’t opt for the Scrambler. With its 1-degree slacker head tube and 10mm longer chainstay, the geometry on the MK6 is dialed, and it perfectly doubles as a rigid singletrack bike and a mixed-terrain bikepacking rig. All the stability, balance, traction, and comfort I experienced on the trail carried over to how this bike handled while riding loaded. I took it on a few bikepacking trips, including one rather speedy two-day ride on the Wilson’s Ramble in singlespeed mode and a couple that were more geared toward party-in-the-woods good times. On one, I loaded it up with fishing gear and a lot of food and drinks. On another, I kept it light and minimal. The bottom line is that it’s a comfortable bike, and the frame handles the extra weight more than fine. I don’t have a single significant complaint other than the lack of lower cage mounts.

Who’s it for?

So, who is this bike for? That’s a good question. While it’s a bike I wish everyone would try, I also realize that riding a rigid mountain bike isn’t for everyone. It makes me think back to my first time riding the incredible singletrack in and around Sedona, Arizona. I was on my rigid Krampus at the time and thought it was the bee’s knees.

However, most of the folks I met thought I was off my gourd. The Stooge MK6 encapsulates all this. With the right mindset, it’s a bike that can be ridden anywhere and everywhere, all the time. On one hand, it’s just a well-conceived, do-all, go-anywhere, low-maintenance mountain bike. On the other, it’s the perfect vehicle for people who want to dig deep into trails, ride mindfully, and figure things out while pedaling in the woods.

- Model/Size Tested: Stooge MK6, 20″

- Actual Weight (Frameset): 10.5 pounds (4.8 kilograms)

- Place of Manufacture: Taiwan

- Price: £780 (~$965 USD)

- Manufacturer’s Details: Stooge Cycles

Pros

- Extremely fun bike—perhaps the most fun I’ve had on a rigid mountain bike ever, or at least since the original Krampus

- A playful yet stable geometry that’s near perfect for rigid trail riding

- Nice tubing selection and design that’s both comfortable and lively

- Original look marries a classic aesthetic and klunker vibes with modern angles

- Love the 2.6 / 3.0” 29er combo

- A versatile platform that’s good for many configurations: singlespeeding, bikepacking, trail bike, etc, etc.

Cons

- No mounts underneath downtube

- Top tube/seat tube junction could be a centimeter or two higher

- Internal gusset at down tube/head tube junction would be a cleaner look

- Small and XL sizes would be nice

- Heavy frameset

Wrap Up

It wasn’t so long ago when all mountain bikes were rigid, but as trail bikes evolved and progressed over the last decade, focusing on speed and “taming the trail,” rigid mountain bikes have largely been left in the dust. The Stooge MK6 reclaims its roots, eschews the constraints of modern bike technology, and essentially reinvents the wheel for riders interested in experiencing all the bumps, undulations, and nuances of the trail.

I didn’t know what to expect from the Stooge MK6, but at the same time, I expected a lot. Fortunately for me, it validated the first side of that statement and satisfied the latter. It was full of surprises, and it didn’t let me down. As I see it, Andy’s obsession with building the perfect rigid mountain bike paid off in spades. Like the band it’s named after, the MK6 is punchy, lively, raw, and is simultaneously ahead of and behind the times. If someone asked me to pick just one bike to spend the rest of my life with today, it would definitely be this one.

Feel free to fire away with questions in the conversation below, as there’s still plenty more to discuss and say about this unique bike…

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.